A Strike is Not a Spell

on the January 30 “general strike.”

adrienne maree brown imagines community organizing as a series of spells. You might use one of brown’s spells for radicals to greet a comrade with gratitude, or to restore your spirit through intense grief.

Spells can be useful. But as we saw on January 30, a strike is not a spell.

Socialists in the US feel powerless, because we are. Only 10% of workers are part of a union, leaving the vast majority to struggle alone or beg for scraps. When we live with this frightening awareness of our weakness as individuals, we turn to another kind of magic, a dark one. We cast the words of our radical ancestors like wishes, emptying them of their meaning, of the years of struggle that gave these words their great power.

“Strike” is one such word. As Joe Burns lamented in his essay, No More Fake Strikes: “Unlike real strikes, which take a ton of work, calling a general strike is apparently a simple affair. A date is picked, a Facebook post is created, the labor liberal press picks it up, and a general strike is born. This raises the question of under whose authority they are being called.”

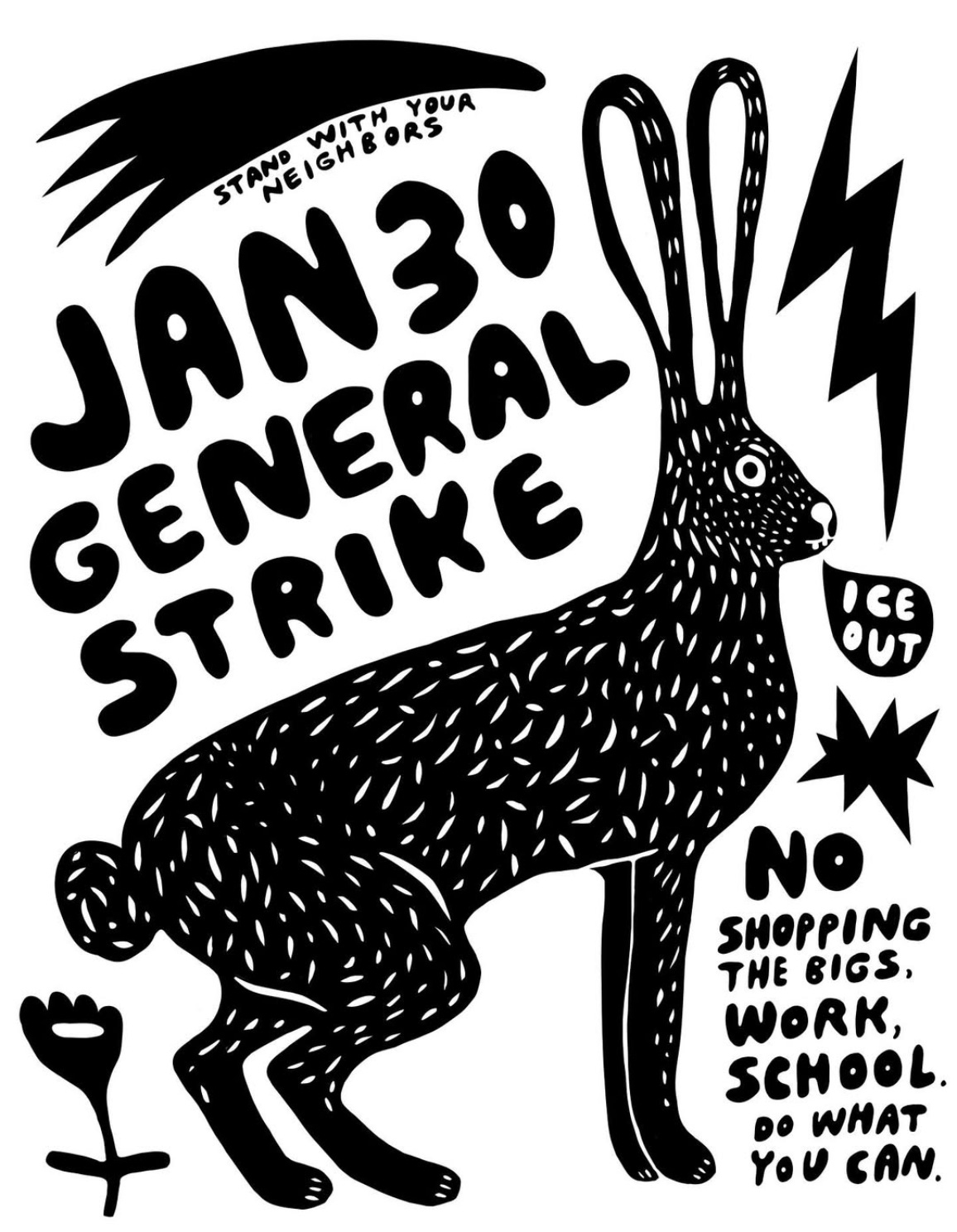

Burns’ 2019 essay meant to criticize a series of forgettable calls for general strikes during the first Trump administration—I had trouble remembering any of them. Seven years later, we found ourselves staring down another nationwide plea, largely circulated on social media, with no apparent endorsements from unions. Thousands of infographics carried the wish for a general strike to protest the atrocities carried out by ICE, casting the strike over the internet like a spell.

As January 30 approached, it became apparent that this nationwide general strike would not have the overwhelming success of last week’s Minneapolis strike, whose momentum it seemed hopeful to build from. The January 23 strike took place in an unusually union-dense city, whose organized workers voted to join a long list of official endorsements, including the first in more than 70 years from the AFL-CIO. Some 100,000 people joined the unions in the streets to protest the murder of Renee Good and demand that ICE leave Minneapolis. It was a historic success, an incredible flex of organized people power.

On the eve of January 30, I began to see some social media influencers backpedal from the strike’s initial demands. If your boss says you can’t go on strike, then just try working slower. Play dumb, Amelia Bedelia, follow exact instructions and nothing more. Quiet quitting, apparently, counts as a strike.

These tactics are not foolish in themselves. Protest movements use aggressive compliance to stall and irritate police during a corrupt operation. Work slowdowns are a historically proven pressure tactic on the boss, but only as a carefully organized mass action with a majority of workers on board.

Small business owners paid particular attention to the January 30 general strike. Whether they saw this as an opportunity to virtue signal to a liberal-left customer base, or just wanted to pre-empt the headache of workers calling out that day, many businesses took to social media to announce their closure for the day. Others posted saying they could not afford to close for the day, but would donate 15% of sales to a nonprofit. Still more businesses encouraged their audiences to go on strike by shopping small and paying in cash. Small Business Saturday, that’ll show the elites.

On January 6, the ragtag group of insurrectionists who landed in DC appeared to comprise realtors, self-employed contractors, small business owners, and even artists. Ariel Pink and John Maus posted videos from a nearby hotel, while Mr. Show’s Jay Johnston appeared in footage from the capitol. Historically, the petit bourgeois class has been a dedicated base for fascist movements. But what’s a small business owner to do when their personal liberal sensibilities put them off the far-right? Floundering for a political identity in the lead-up to January 30, the sympathetic petit bourgeois resolved that they would appropriate the language of working-class struggles. They joined the “strike,” and either denied or misunderstood their historical class position in subjugating these very movements.

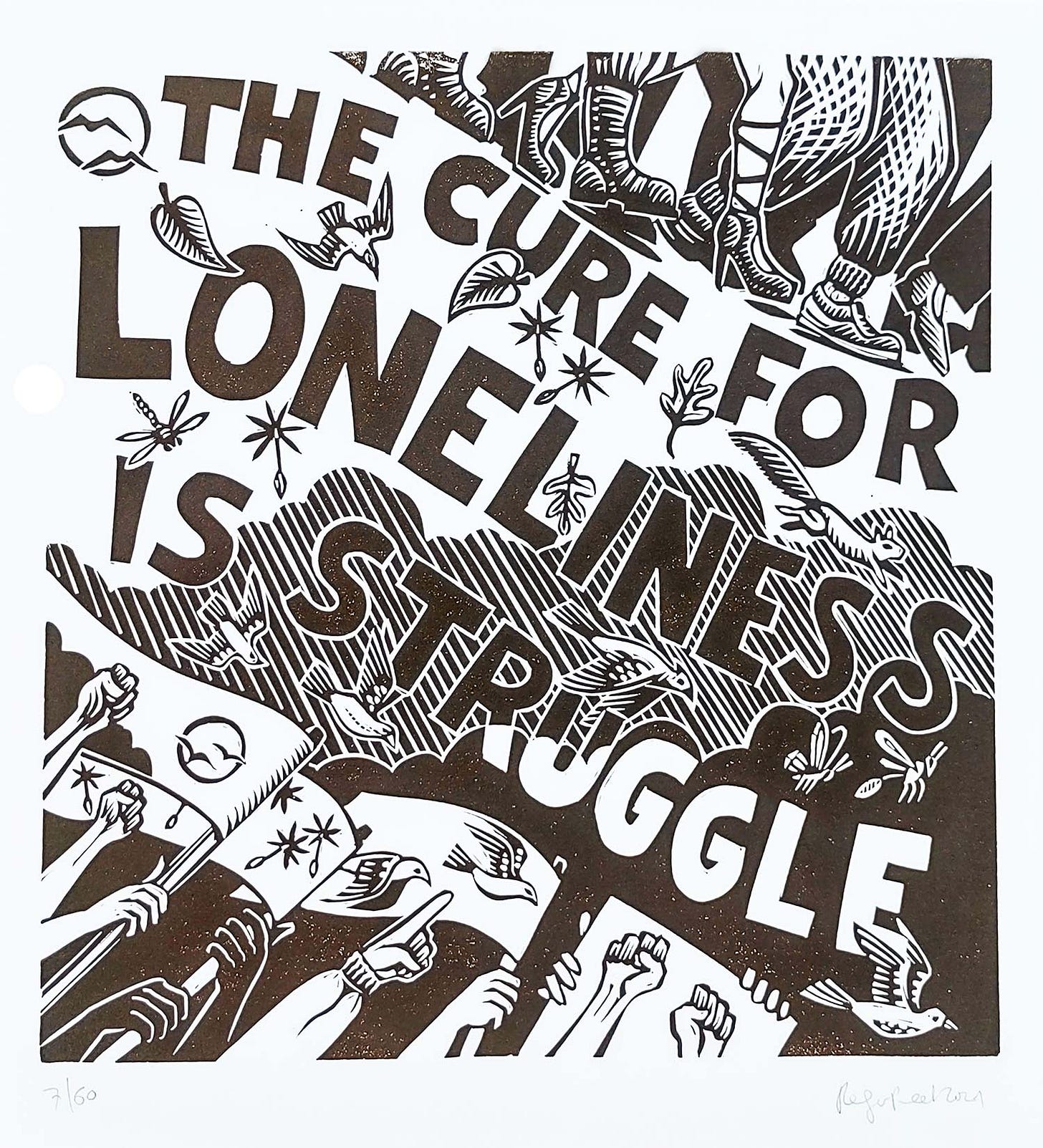

Fellow labor-socialist artist Roger Peet took to Instagram with sharp criticism the day before the “strike.” I owe all credit to Peet for the metaphor of magic to describe this behavior: “everyone wants a magic spell to do something about the way things are. But there is no spell. You have to organize.”

As professional artists who make a living from our labor craft, Peet and I both might resemble small business owners more than workers, depending on the day you ask. Artist-insurrectionists like Pink and Maus were eager to fall on the capitalist side of that thin line, but even if you choose to fall on the workers’ side, it’s critical to understand your role in a strike. Which is, essentially, that you don’t have one.

Artists can certainly benefit a strike. I’ve been doing solidarity design work for my central labor council to support UAW Local 42, in the event they decide to strike. If you’re a cook, you can take a shift in the strike kitchen. If you play guitar, go strum on the picket line (if you’re good).

The same goes for small business owners: you can always donate to a strike fund, open your doors as a meeting venue for workers, or put a union poster in your window. (My boss at the time did this for the UAW election, go off Andrew!)

But only the worker actually goes on strike. As such, the only people who should call for a strike are the workers who will be striking.

Burns wrote: “Most union constitutions have detailed rules and procedures for striking, including rules on when and how strike votes should be conducted. While some may dismiss this as mere bureaucracy, strike votes are taken seriously by most unions because the stakes are so high for the affected workers. By voting to strike, a group of workers commits themselves to a battle which has major repercussions for their individual and collective futures.”

I don’t argue to discourage anyone from taking action, however disorganized, spotty, or trivial that action might be. In a moment of gut-wrenching collective weakness against the unspeakable violence carried out by ICE, I don’t blame anyone for reposting an infographic or slowing down at work. It’s simply not worth the energy to go after well-intentioned members of my own community.

What I do want to scream is that a strike is not a spell. A small business cannot strike. A single worker cannot call a strike. Nor can a union president, a politician, a celebrity, say the magic word and have it be so.

A boycott is not a strike. Shopping small is not a strike. Working slow is not a strike. Elite capture is a system of appropriating and watering down radical language as a way of disempowering a movement. Don’t let them take this word from us. Don’t let them dull down the incredible power of workers going on strike, forcing the gears of capitalist wealth production to a grinding halt. Don’t let them lie to you about how a strike happens: the many hours of organizing to build trust and capacity among a group of workers, and the collective decision that leads to that green light.

If you’re feeling powerless today, please talk to your coworkers. Maybe one day soon there will be rumblings of a general strike in your city. If you have a union by then, or even a game plan you came up with together in Dan the Line Cook’s living room, you’re already more powerful than a thousand social media infographics could ever be.

Power concedes nothing without a demand—and that demand is not a word, not a spell. It is a strike.

Labor Intensive Recommendations

Salt of the Earth (1954) — incredible feminist perspective on a union struggle.

The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway — favorite book I read last year.

A YMCA membership — this will fix you.

Excellent work, as always. Thank you for the gift of this essay 🖤

Top of my email as i get off work today. Great stuff, totally agree. They can never take the word and its power from us.