Gaza in Ink: an Interview with Kholoud Hammad

The 21-year-old Palestinian artist has lived through a genocide, and she wants you to see her drawings.

In case you don’t read all the way to the end of this interview, here are some quick ways to support the artist:

Purchase Kholoud Hammad’s risograph prints from Gerard D’Albon.

Donate to Kholoud Hammad’s fundraiser and get risograph prints as a perk.

Follow Kholoud Hammad’s Instagram and share her work.

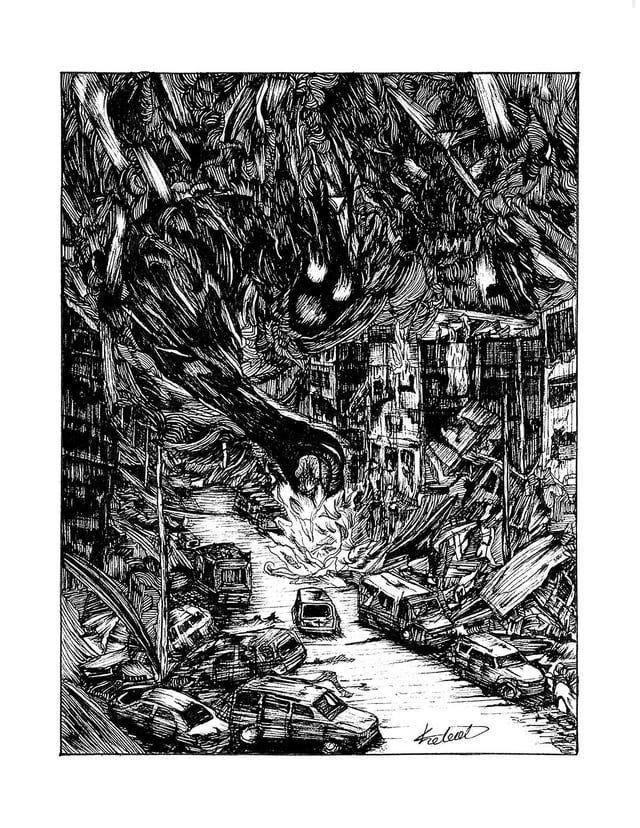

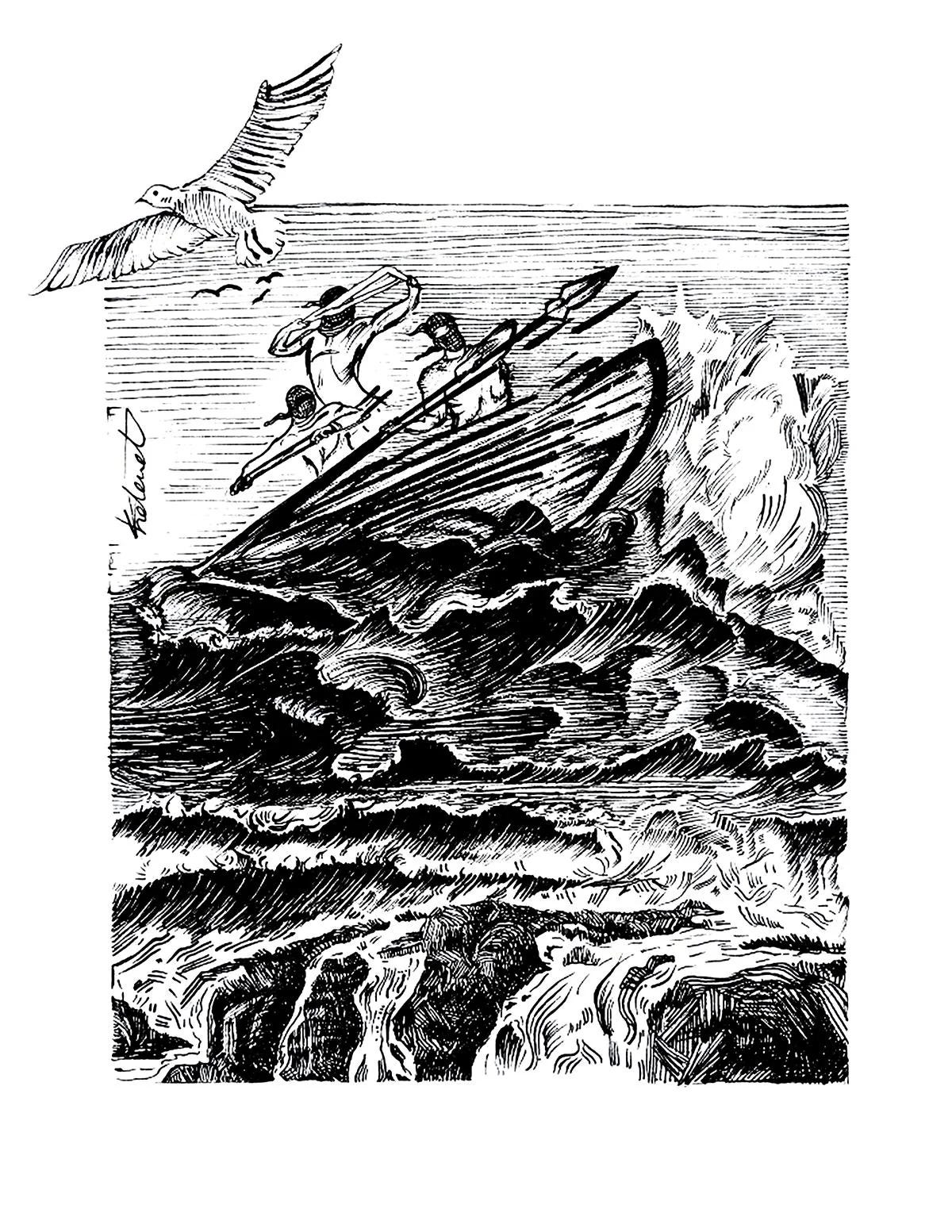

In my last article, I mentioned the work of Palestinian artist Kholoud Hammad. I recently ordered two of her illustrations, Gaza’s Nightmare and Ocean, from Gerard D’Albon: an NYC-based artist and DSA member who distributes risograph prints of Hammad’s expressive pen drawings.

D’Albon told me he first noticed Hammad’s work on the Flyers for Falastin Instagram. He reached out directly to brainstorm ways to support and raise funds for the displaced artist’s family.

“After confirming I could wire funds to their bank in Gaza, I reached out to a few Risograph labs who offered free printing for her artwork, and since then I have been selling prints online and at local markets to hundreds of people,” D’Albon said.

“I’ve been able through selling Kholoud’s art and my own as well as direct donations to raise over $7000 for her so far, as well as another $7000 from my own art sales for other direct aid to Gaza.”

A lot of my own artistic inspiration comes from trawling the Palestine Poster Project Archive, which covers decades of visual artists organizing against the occupation. Many of these artists are still living; since Al-Aqsa Flood and the genocide in Gaza, I’ve seen a wave of recognition in the US for people like Sliman Mansour, now in his 80s.

For every artist like Mansour who lived long enough to share their work with an international audience, hundreds more have died—like digital illustrator Mahasen Al-Khatib, 24, who was killed by an Israeli airstrike at Jabalia refugee camp in October 2024.

Then, there’s the unknowable number of Palestinian artists who died before they had the opportunity to practice art at all. Half of Gaza’s population are children, and the death toll since Israel’s genocide October 2023 includes thousands of babies and toddlers. It’s a harrowing reminder of why poetry is the most popular artistic medium in Palestine, where physical artworks are routinely buried under rubble, and art-making materials are as scarce as food and medicine.

Despite these conditions, Kholoud Hammad is still drawing. I reached out to the artist to learn more about her life and practice over the last 17 months, many of which she spent in a tent in Jabalia.

What’s your name? How old are you, and where in Palestine are you from?

KH: My name is Kholoud Mohamed Hammad, and I am 21 years old. But age doesn’t define maturity—war forced us to grow up too soon, seeing and experiencing things the world has yet to understand. I am from northern Gaza.

What was life like at home, before Al-Aqsa Flood?

KH: We lived under siege and restrictions, yet we still found ways to live, sharing dreams and ambitions. My brother was an inseparable part of my days—my source of support and the one who completed my successes. He filled our home with life, and his reactions to my achievements are still etched in my memory.

Life was never easy, but we had hope. I excelled and graduated as the top student in my Graphic Design department. My home in Jabalia was my little world.

When did you first start drawing?

KH: I have been drawing since childhood, but it became my true passion as I grew older—especially when I realized I could use it to express Gaza’s suffering and resilience.

Are you the only artist in your family?

KH: Yes, I am the only artist in my family, but they have always encouraged creativity and supported my passion.

Are there other artists you look to for inspiration?

KH: My greatest inspiration comes from our reality—from the resistance I saw in my brother’s eyes and from the streets of Gaza, which tell a thousand stories. I love art that reflects just causes, and I draw inspiration from every artist who carries their cause in their brush, just as I try to do.

What kind of artwork were you making before you graduated from university? What did you hope to practice as a career?

KH: Before graduating, I explored and created many types of art using different colors, materials, and techniques—such as blending, color fields, portrait drawing, engraving, and printmaking with various mediums. It was a journey that taught me art has countless ways to express what’s inside us and reflect our identity.

I’m grateful to have touched the surface of these vast artistic seas, but I knew I had to choose one path to master. Amid this war, I found ink art to be the most suitable, as I could easily carry my tools in my displacement bag.

As for my career, I have always loved both art and prints. My dream was to merge art with design, creating unique, art-infused designs as an( Illustrative Graphic Designer). I was also passionate about motion graphics, which influenced my art, making it dynamic and full of movement.

I once dreamed of securing collaborations and job opportunities both locally and internationally. I did land some jobs, but the war halted my journey—especially after enduring the trauma of losing my brother and my personal laptop when our home was completely destroyed. Still, I didn’t stop. It was a risk, but I searched for a nearby place with solar-powered charging to keep sharing my art despite this nightmare.

After Al-Aqsa Flood, you and your family were displaced from home. What was life like during this time?

KH: We lost our home and vehicle in Jabalia, forcing us to walk day and night, searching for shelter. We had no stability—we were surrounded by fear, displacement, hunger, and the sounds of different weapons. We could even tell each weapon apart by its sound.

Sleeping in a room with three families was considered lucky, as the overcrowded school shelters housed even more. I remember once sleeping in a classroom packed with seven families. It felt awful to finally find a place to rest, only to be forced to leave within hours or days. We had to move quickly to avoid being hit, carrying whatever we could afford—because you can’t fit everything you need into just two or three bags. If only one could pack their entire life and family into a single bag…

We were trapped between artillery shelling on one side and bullets piercing through shattered windows on the other. The military was wiping out entire residential blocks around us. We tried to stay as long as possible wherever we took refuge, but being surrounded from all sides and seeing the enemy advance left us no choice but to flee—like a relentless monster hunting us down, tracking our every move through warplanes. I captured this nightmare in my painting Gaza’s Nightmare. It was a scene we relived with every displacement.

As we fled through the narrow streets of Jabalia, we kept hearing news of loved ones lost. I lost my brother on November 21, 2023, in the early days of the war. At that moment, I couldn’t comprehend what was happening around me. I broke down—I had lost a part of my family. There is now a deep void in our lives without my brother, Mustafa. His absence tore through my soul. The way he reacted to my achievements always motivated me to keep going, and losing him was a shock I’m still struggling to process.

What we went through is beyond what any human mind can endure. Life felt like it was slapping us over and over again. We will never forget this suffering. But despite everything, our resilience never faded. Deep in our hearts, we hold onto the certainty that, no matter how long it takes, we will return to Jabalia.

What did your drawing practice look like over the past 16 months? What materials did you use, where did they come from, and when did you have time to make drawings?

KH: It was tough—almost insane—to hold a pen and draw a line while surrounded by war, with my life at risk in northern Gaza. But every Gazan resists in their own way. I resist with my pens, my art, and my patience—fighting to document the beauty and resilience of Palestine, the symbols of our identity that deserve freedom. Yet, alongside this resilience, there is immense suffering.

I relied mostly on simple tools—black ink and pencils—because accessing advanced art supplies was nearly impossible. The sketchbook I used was a gift; I started drawing in it because it was small enough to carry in my displacement bag, ensuring I wouldn’t lose it like I lost everything else. When my pens ran dry or my sketchbook filled up with drawings, I replaced them with whatever I could buy from the little aid I received.

I didn’t use colors because they were too expensive. But that didn’t stop me. Whenever I felt the need to add color, I seized any chance I had—borrowing a friend’s laptop to color my work using design software. It wasn’t professional since I never had the time to perfect it, but it was enough.

I tried to find any small space to draw whenever I could—whether it was a tiny notebook in a crowded corner or during brief moments of ceasefire.

Tell me about the themes of the artwork you made. What did you hope to capture or express in your drawings?

KH: My art collection, which I named "Shadows Under Fire," reflects the suffering and resilience of my people under the nightmare of occupation. It is a testament to a cause deeply engraved in our minds. I firmly believe that art is a vital tool for preserving national memory and reaffirming the right to freedom and dignity.

These paintings were born to embody the spirit of endurance and hope in their details. My work is inspired by the harsh reality we live in—a life marked by displacement and exile, surrounded by painful scenes. This is why my art is a response to what I have personally endured. Every stroke carries a story of struggle, a reflection of the hardships I faced, and an expression of our unwavering belief in return despite everything we have been through.

I wanted to show the world that Gaza is not just numbers in the news—it is a place full of resistance and beauty.

I deliberately chose black and white because it felt like life had lost its colors. The only other color I use alongside black is red—to represent the blood I have witnessed in my early twenties (ages 20 and 21).

Did the funds from selling these drawings help your family? What were you able to do with the money raised?

KH: With the help of some people who supported my art, I was able to sell my work and use the money to buy basic necessities for my family, like food and essential supplies. Fortunately, a few days ago, we found a home at a reasonable price, and we are paying the rent with this money, along with the continued support from Gerard.

I hope this support continues so we don’t have to return to living in tents—life is still very unstable. I also used part of the money to buy art supplies so I can keep creating. Art is not just a source of income for me; it’s also a way to express and process everything we are going through.

Additionally, I donated some of the money to people around me who are struggling to afford basic necessities. Prices are still extremely high and haven’t returned to normal, and at the same time, there are no jobs available.

Now that Israel has agreed to a ceasefire, is your family able to return home? What is the next step in your journey?

KH: Our home in Jabalia is gone, completely destroyed, like thousands of other homes. There is nowhere to return to right now, so we are trying to find temporary shelter. But life is still unstable, filled with daily struggles and losses.

For me, the next step is to keep creating and developing my art—to share our stories with the world. I am also searching for ways to support myself and my family during this difficult time. Despite everything, I am determined to rebuild what we have lost and pursue my dreams.

I’m going to encourage people to buy your work and donate to your fundraiser. Is there any other way people in the US can support you?

KH: Every bit of support makes a difference. My family needs ongoing help each month so we can start rebuilding what we lost and find stability again. We just want to regain the normal life that every human being deserves. But we can’t do this alone—we need continuous support.

As for me, I dream of developing my talent, turning my art into digital illustrations, and combining it with design. To do that, I need an iPad for drawing and a modern laptop for design. Achieving this dream feels painfully slow under the current circumstances in Gaza.

I hope that one day my art and designs will reach a wider audience, leading to collaborations or a job that would allow my family to live with dignity. If my family finds stability, I will finally have peace of mind in this struggle."

Is there anything else you’d like to share with people in the US? What do you want us to know about you, your family, or life in Gaza?

KH: I want them to know that we are not just numbers in the news. We are people who live, dream, and laugh—even if laughter is stolen by this harsh reality. We try to find beauty amidst the destruction. Despite everything, beyond the ruins, Gaza still beats with life, art, and resistance. Every person here has a story. I want them to see Gaza through our eyes, to hear our stories, and to understand that their support can make a real difference in the lives of people like me.

Thank you to everyone who believes in justice and freedom, to those who have raised their voices for what is right, and to those who have not ignored our suffering. Our gratitude is boundless to those who have stood by humanity in its hardest times.

I want them to know that I turn every obstacle in my path into a solid rock that I stand on to rise higher with my achievements—with the support of my family and people like you. I am a creative individual, standing on a strong foundation, which will only grow stronger if given the opportunity to share my art and designs with the world.

— Kholoud Hammad, interviewed March 2025.

Palestine’s small cohort of visual artists are regularly displaced; many of them much further than Hammad from her home in northern Gaza. Some, like artist and archivist Samia Halaby, traveled to the US, where the fine art economy operates with unchecked anti-Palestinian discrimination. Halaby’s very first painting retrospective, slated to open at Indiana University in February 2024, was abruptly canceled amid Israel’s genocidal attack on Gaza.

Gerard D’Albon reflects on these art world failures as he works to build solidarity with artists in Palestine. “I’ve been disappointed to see how many artists and cultural institutions remain silent on this ongoing genocide when it’s so crucial that we use our practice and platforms to fight against these injustices perpetuated by our own country.”

D’Albon told me that in 2024, he worked with Gazan illustrator Maisara Baroud to project the artist’s work on the facade of MoMA. Next, D’Albon hopes to organize a group exhibition of Palestinian artists in New York City.

I’m asking my readers to join me in supporting Kholoud Hammad’s family. I am grateful to have sold prints of my artwork to thousands of people, and as much as that support has meant to me, it’s only a fraction of what it would mean to Hammad to have her work purchased and shared widely in the US. As Hammad said herself, this sustained flow of income is what her family needs most as they navigate each new day in Gaza.

Here are some great ways to support the artist:

Purchase Kholoud Hammad’s risograph prints from Gerard D’Albon.

Donate to Kholoud Hammad’s fundraiser and get risograph prints as a perk.

Follow Kholoud Hammad’s Instagram and share her work.

Thank you, and solidarity forever!

Awesome interview! Learning more about art as a medium of social change … very cool

Great interview. Kholoud’s work is beautiful and depressing to think that it’s their current reality.