Hell is Being By Myself

Thoughts on utopia after a residency.

I just left my MacDowell Fellowship, where I spent a month in New Hampshire working on a rug titled “Gospel.” I intend to write about this piece soon, because it’s layered with plenty of meaning. But today I have some feelings about the residency to share.

Over the last few years, I’ve been feeling the slow creep of social isolation into the rhythms of my life. After COVID-19 emerged, I watched all of the benches vanish from Philadelphia’s subway stations. I didn’t have a lot of spending money for restaurants and bars, but there weren’t many other places in the city to hang out after dark. Of course, when I do manage to go out, I’m still afraid of getting sick.

After I moved to a car-dependent city, I noticed how competitive it feels to drive. Instead of making a shared journey on train cars and trolleys, everyone is just in each other’s way, fighting for lanes, weaving through traffic. I joke about wishing cars had the option of a friendly sound. When all you have is a horn, everything looks like something to honk at.

I started freelancing at home, which is such a luxury, but it also means I have nowhere to go and nobody to see. On the days that I go to the coffee shop, I wonder if the baristas know how excited I am for our clipped conversations across the bar.

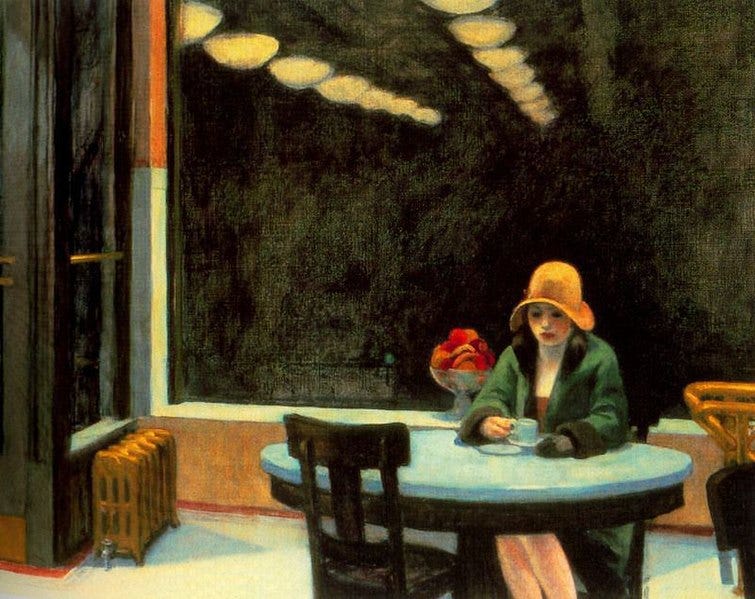

I’m beginning to understand Edward Hopper’s paintings on a new level, which is probably not a good sign.

At the end of last year, I got the news that I was invited to stay at MacDowell. I’d be there with a group of other artist Fellows, with free meals prepared for us daily, and I’d sleep and work in my own little cabin on the hundred-year-old residency grounds. I didn’t have to pay anything for it.

It was an incredible privilege. So I went.

My first observation of MacDowell was how much time I gained back in a day when I wasn’t responsible for feeding myself. Buying groceries, planning meals, cooking, cleaning, dishes: it was all taken care of by the residency staff.

With no wage work and no reproductive labor (besides a weekly trip to the laundry room), I was solely focused on two things: art-making and socializing.

So this was utopia.

As I began making friends with other residents, we remarked on the shared feeling that we were being observed, like lab rats or reality show contestants. We could have been samples in a study on how people would move and think and interact without the structures of capitalism imposed upon us.

With no alarms, clock-ins, or appointments to orient around, we naturally created a shared routine at the residency. The activities we liked evolved into rhythms and rituals, and our jokes and conversations flowed into a kind of culture that was unique to us.

I had forgotten what it was like to talk to somebody every morning over breakfast. Every evening, I could get to know a new person, and we could linger for an hour if we were having a really good conversation. We could open a bottle of wine and talk all night. We had nowhere to be. There was nothing to worry about.

MacDowell’s motto is “freedom to create,” which I honestly found cheesy at first. But in retrospect, it’s exactly true: freedom is the most precious gift that MacDowell offers. The residency made us free from laboring in a capitalist world, and by extension, the social alienation that comes with it.

We weren’t exhausted after our busy shifts. We weren’t too broke for the show cover or the bar tab. We weren’t competing for scarce opportunities. We were our best selves, giving our energy over to creative passions and socializing, instead of prioritizing money and work. I would argue that beyond freedom to create, we had the freedom to connect and the freedom to love.

I’m coming home from MacDowell with something like survivor’s guilt on my mind. It felt like I got a glimpse of how all of our lives could look; if we only had the luxury of laboring only to sustain our community and its needs, instead of having everything extracted from us for profit.

I wish I could turn around and give that gift to everyone else in my life. How many rideshare drivers, food service workers, and gig economy employees would spend their whole day making art if they had that freedom? Why can’t we all have it?

In this lonely moment, when it feels like the world is pulling everyone further apart, I’m starting to think that any gesture toward community and togetherness is a radical thing. Public spaces where we can cross paths with strangers, free time to grow deep relationships with neighbors, and gatherings where we can support other workers through shared struggles: these are some of the richest, most fulfilling parts of life. More than that, they’re all basic foundations for a socialist world. They threaten the rule of capitalism.

If sharing our lives in community is what makes utopia, then the extreme social isolation of late capitalism must be Hell on earth. I think we all have a responsibility to push back, to get the closest we can to Heaven while we’re here together.

I’m not sure exactly how to close this one out, so I’ll leave you with something I wrote after I had a Delta-8 gummy and thought I was being profound:

—

Orienting myself within a group of strangers always feels like rediscovering who I am. It happens at an artist residency, a summer camp, or at the start of a new job. By the time I feel like myself again, I find that I’ve actually changed in the process, becoming someone new and different.

It feels so permanent, I’m convinced that I’ll continue my life as this new and improved version of me. But when I quit the job, or head back home, the new me never really survives the journey. I shift back to my old habits almost immediately. I try to hold on, but that ephemeral version of me is like a fistful of sand.

In the first few days back home, when everything still feels vivid and warm, I soak in the memory of the mysterious me who was called into being by that loving community—or at least, by the versions of them that came alive for me.

I think about this all so much in my day to day as a freelance textile artist. I’ve had years when I was living in strong community; now is not one of those times. I’m very intentionally trying to get back to that— and I’m finding it really hard! The one thing that gives me hope is teaching. Teaching my art allows me to connect with students, have that meaning-making shared in the pursuit of art together, and socializing along the way. I’m so happy I found your work today!

Thank you for this, having also just returned from a residency, I was almost annoyed at myself at how quickly the ferocious pace of work came back to my body. The bubble of the isolated but together artist bubble always seems to burst 💔