Mill Town

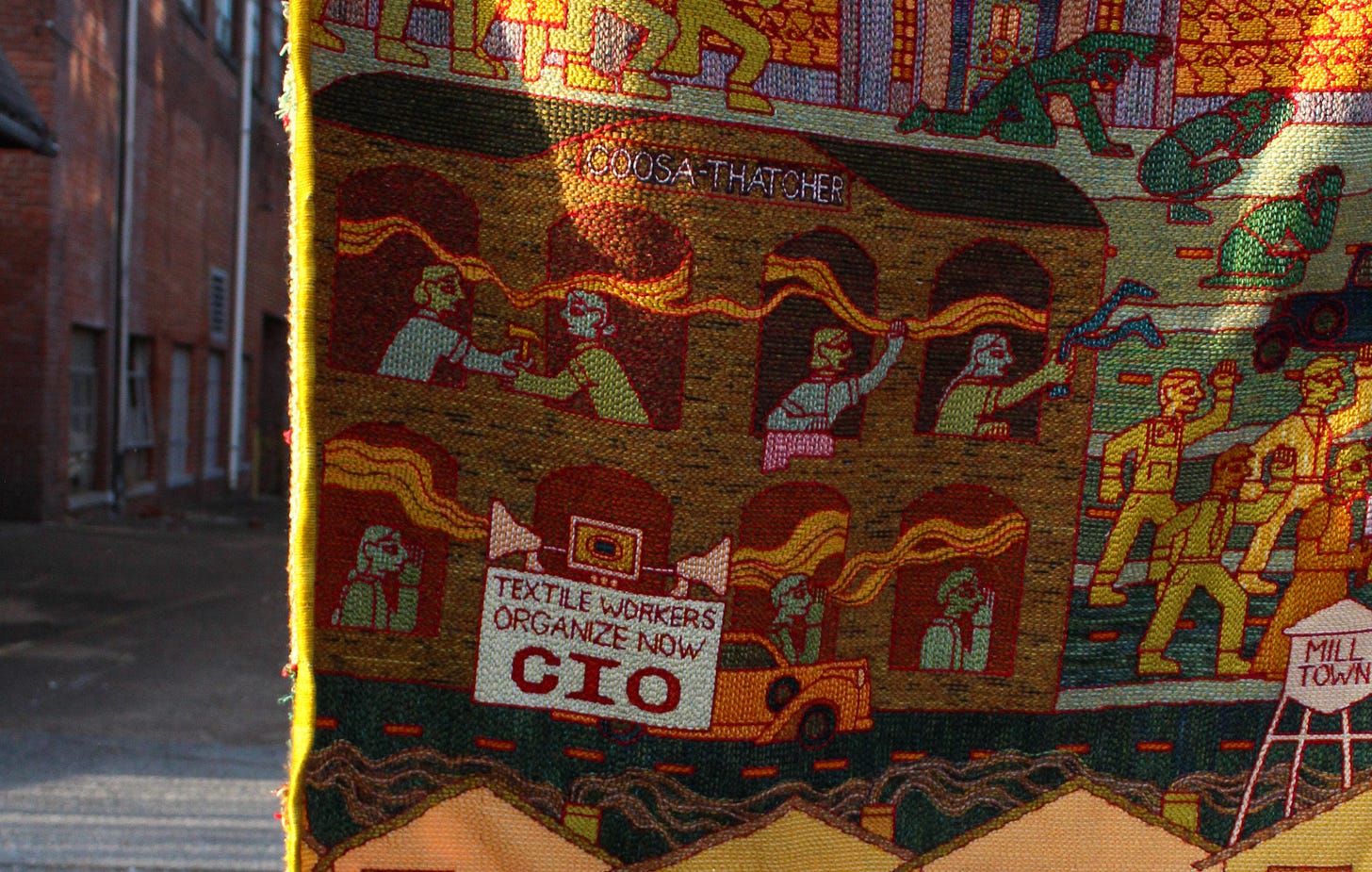

A tapestry about the textile strike of 1934 in Chattanooga.

Every day, when I drive from my house to my studio, I pass the Mill Town water tower.

I’ve been curious about it ever since I moved back to Chattanooga. It’s a bright white beacon with red lettering that jumps out from the deep green mountain ridge, visible from the highway, where it looms over factory ruins in a slowly gentrifying neighborhood.

What is Mill Town? — that’s probably what the developers hope you’ll ask. The snappy logo appears on signage around an ongoing construction project underneath the tower. In short, it’s luxury housing: the same kind of townhomes that have popped up all over the city since 2020, when housing costs began to skyrocket.

But with its name, Mill Town betrays another story: a previous life of this neighborhood, at the height of an old industry, when work and the social structures around it looked completely different. It sits on the bones of the original mill town, or worker village, that once surrounded the Coosa-Thatcher textile factory.

About a century ago, employees at Coosa-Thatcher rented modest homes around the factory for peanuts, lived next door to their coworkers, and met up every morning for the short walk to clock in. They bought groceries and household items at the company store at prices set by the mill. They spent leisure time at the mill gymnasium and park. Some towns even had their own sports teams where textile workers competed in a southern league against other mills.

With all these amenities built into their communities, workers in mill towns lived in a complex, paternalistic relationship with the company. The boss was also their landlord, which meant that organizing against him had an extra layer of precarity. If you were fired, you could lose your home the same day. The Uprising of ‘34, which documents the national textile strike as it played out at a mill town in North Carolina, features workers who recall young children dying of exposure after the mill evicted their families in retaliation for organizing.

The company ruled with fear, but it also maintained control by giving out calculated benefits: in the textile industry, women had an unusual opportunity to work factory jobs for similar wages to men. For the most part, this only applied to white women. Black workers were integral to the mill town, often laboring in homes and laundries as a service class, but rarely making it to the factory floor. Even as conditions in the mill worsened and injuries were common, white women feared losing their better-paid position in the town’s hierarchy. Somebody else always had it worse.

It’s hard to imagine how textile workers, as they lived under the eye of the boss and fought over slivers of privilege, got away with any organizing. But as I was determined to show in my tapestry, they pushed through the fear and division to join in militant class struggle. In 1934, textile workers launched the national strike that stretched from the storied bread-and-roses ground of Lowell, Massachusetts to dozens of mills in the Chattanooga area.

To get the word out about the strike, the CIO launched a strategy of driving sound trucks in circles around the southern mills. Through megaphones attached to the top of the vehicles, the trucks blasted a recorded message up to factory windows, where workers poked their heads out and listened to the call to organize. I have a photograph of the day the sound truck came to Coosa-Thatcher, and the scene made its way into my piece.

While I worked on the tapestry, I thought about all the ways textile mills have, literally and figuratively, shaped the city. All over Chattanooga, you can find the ghosts of these company towns where life was arranged around work. I visited one of them recently to talk to Peggy Douglas, a local organizer and playwright who spent years working in a Knoxville knitting mill.

Now Peggy lives in Lupton City, a tight-knit neighborhood planned around the old site of the Lupton mill. I’m intentionally using the pun, “tight-knit,” because I also thought about titling my tapestry something like “The Social Fabric.” It’s striking to realize just how much of our language about community and relationships comes out of textile metaphor. It feels very appropriate to describe how people’s lives in Lupton City were deeply interwoven, interlinked, and bound up together by the work they did at the mill making nylon fabric.

Peggy told me she feels comfortable living in “the village,” where she’s almost naturally organized with her neighbors through the layout of the neighborhood. In the four years since she moved in, Peggy and her fellow villagers are already very close, and have taken collective action against some of the eager developers looking to add new, shoddy structures to the old mill site.

After she worked in the knitting mill, Peggy got involved with Highlander Folk School: an organizing center that once stood about an hour from Chattanooga on Monteagle Mountain. Today, it’s moved to the part of East Tennessee I’d characterize as “greater Dollywood,” and continues to serve as a training ground for southern organizers as its communist founders in the 1930s intended.

By the time Peggy arrived at Highlander, the school was directed by Myles Horton, a faith leader and beloved movement hippie who leaned heavily on music and singing as he trained up organizers. It was Myles Horton’s autobiography, The Long Haul, that gave me another incredible story about Chattanooga; which I instantly knew I had to record in tapestry.

One day during the great 1934 textile strike, a dramatic scene unfolded at a mill up in Daisy, Tennessee: now part of Soddy-Daisy, just 30 minutes from Chattanooga. Myles Horton brought a cohort of strike supporters down from Highlander and marched with them on the picket line outside the factory. They were met by armed thugs who attempted to push back and intimidate the crowd of workers. Shots rang out, and instead of putting up a fight, police on the scene hid themselves in ditches. The workers dropped to the ground in terror.

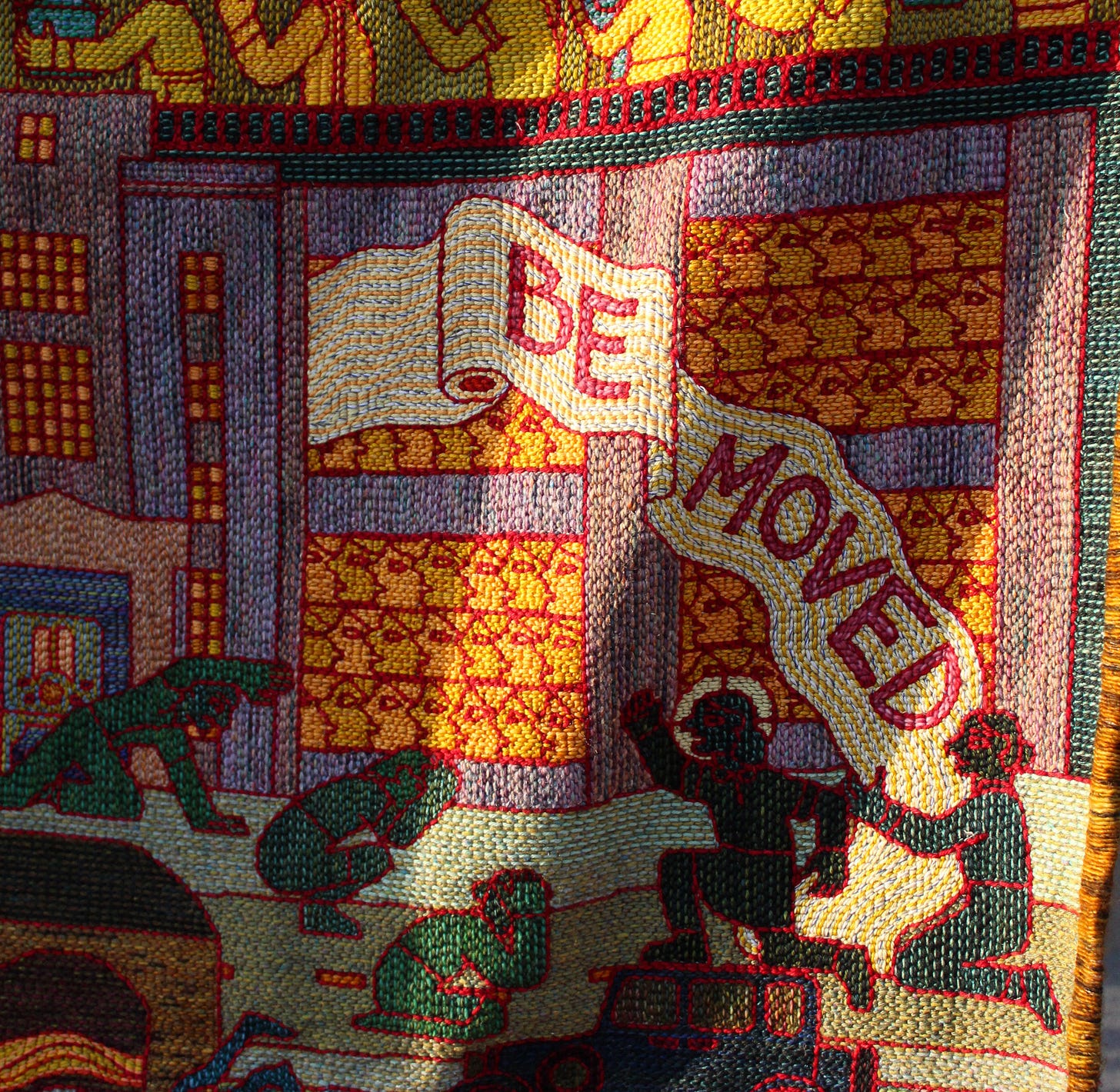

As Myles Horton tells it, there was a brief moment of silence at the Daisy mill, and it seemed like the company might have succeeded in breaking up the picket. But then, a small group of workers stood up again and started to sing. Horton doesn’t remember who it was, exactly, who began the opening lyrics of We Shall Not Be Moved, but this was the first time the song, which likely came about as an African American spiritual before the abolition of slavery, was ever used at a strike.

More people outside the Daisy mill stood up and sang together, and in a matter of minutes, the picket was back on. We Shall Not Be Moved entered the canon of protest songs that transformed lyrically as it moved through the south, bringing the spirit of freedom from slave rebellion to gospel choir to picket line. Throughout the 20th century, it made appearances at coal mines, auto plants, and civil rights marches. According to Ballad of America, We Shall Not Be Moved was the last song to play on Chilean radio before the devastating military coup in 1973.

I began the “Mill Town” tapestry right after I finished my piece about Volkswagen Chattanooga, and I found many connecting threads between these stories. Textile mills used to face similar organizing challenges to auto plants today: the industry broadly covers an incredible variety of jobs, skills, and materials. Workers in garment mills might not recognize anything about the process of making nylon or hosiery, just like someone on the floor at a battery plant can’t easily pick up a shift making the Volkswagen iD-4. It’s difficult for workers to line up demands across such diverse lines.

Still, something about today’s Volkswagen plant rhymes with the old Coosa-Thatcher mill. Workers may not live at the factory anymore, but they might spend time at the on-site gym, cafeteria, and doctor’s office. Many get to work in a car they purchased with a generous company discount. Though there are many good reasons they want a union, Volkswagen employees also know they’re working one of the best jobs in Tennessee; that if their plant shuttered, they’d have trouble finding similar wages and benefits anywhere else.

After all, auto work is one of the last manufacturing jobs that hasn’t been totally offshored by companies looking for cheaper labor outside of the US. Arguably, the auto companies have instead “offshored” their plants to the south: fleeing union-dense northern cities like Detroit for America’s internal colony, where they can pay workers some of the lowest wages in the country to labor in more dangerous conditions than in other states.

When Volkswagen workers voted to join the UAW, it was like I got a glimpse of that class war that an old generation waged across the south in the 1930s. Stanton Smith, a labor organizer and AFL-CIO official who helped form the first teachers’ union in Chattanooga, recalled in his oral history: “I don’t think the people of this country realize how close we were to a revolution in 1932. We were right on the verge of it, and if it hadn’t been for Roosevelt and the New Deal, I think we would have had a revolution in this country.”

There’s folklore that says Chattanooga is one of the most haunted places in the country, crowded with ghosts left behind by the Trail of Tears, chattel slavery, and civil war battles. But when I walk around what’s left of the dilapidated mills, I sense another kind of spirit. It’s the union fire that burned on this same ground, and I like to think it never left.

“There are peaks and there are valleys. Right now we are in a valley. Not many radicals today—a lot of reformers, but not many radicals. I’ve had two wonderful experiences, two social movements—the union movement in the early days and the civil rights movement. I keep hoping I can get in on another one. But it better hurry…I’m ready and waiting.”

— Myles Horton

I got these images of “Mill Town” at Richmond Mill, also known as Peerless Woolen Mill, in Rossville, Georgia just south of Chattanooga. In 1935, a striking worker named Columbus “Pink” Walker was murdered on the picket line at this factory. It stands mostly dilapidated, with a slow effort from the city to transform its shell into retail space, housing, and artist studios.

I collaborated with Tori Vintzel, who took all the photos and video of the piece around the mill. It was a really special way to document the tapestry.

Labor Intensive Recommendations

New Art in an Old Mill — Gina Lerman (lermworm) writes a great newsletter, apparently in eerie synchronicity with mine.

After Effects — Peggy Douglas’s new play centers survivors of gun violence.

From The Ashes — Sarah Jaffe’s new book on grief and revolution.

Can’t decide if your art or writing is better. Both are amazing.

The photos of this piece are gorgeous and the historical perspective is powerful. Fantastic work!